Qomolangma is the Tibetan name for Everest.

Lhasa to Everest, rerouted

Does travel change a person? Absolutely! It has changed me over and over. My priorities have shifted. Many cultural differences now feel

so familiar and natural. I've learned that logic is not absolute, but very much depends on its roots.

There was a time when I couldn't get enough of books like Jon Krakauer's Into Thin Air and Jamling T Norgay's Touching my Father's Soul, and I watched and re-watched movies like Everest (1998). I've never managed to run for more than 20 minutes and never attempted a climbing wall at a gym, so the closest I would ever be able to get to is Everest Base Camp.

In 2012, this decades-old dream felt within reach. This time, we finally got our visitor permits for the Tibetan Autonomous Region (TAR). It took us almost 24 hours to cover the 2000 km distance between Xining and Lhasa on the world’s highest railway through the breathtaking scenery of the Tibetan Plateau. Several times during the journey we passed the 5000 m elevation mark which also helped with our acclimatization.

The TAR is usually closed for foreigners in spring, so we were among the very first ones of the season.

Our accommodation in the old part of Lhasa was simple but clean and convenient, run by a friendly Tibetan lady and her family. Life was humble. Lacking private rooms, at night the wooden bench in the restaurant served as a bed for the owner's mother.

Rama Kharpo Hotel & Restaurant in Old Lhasa, Barkhor

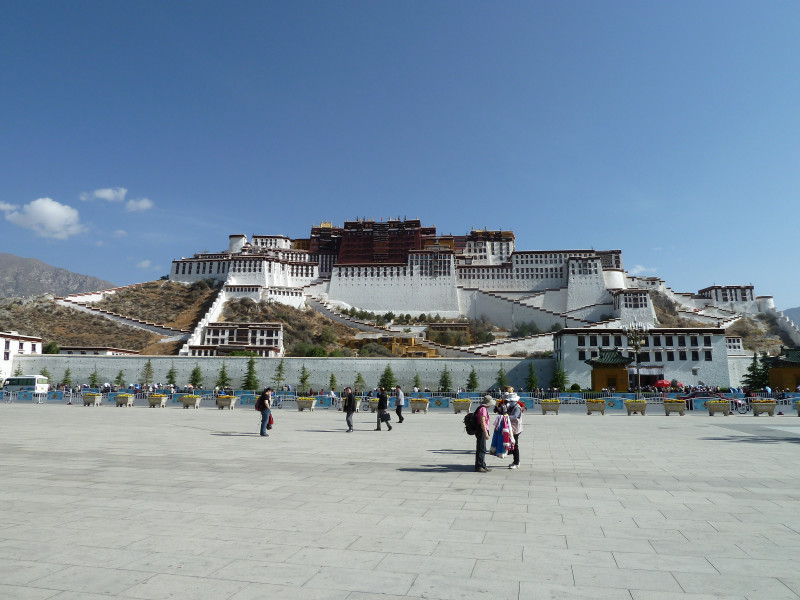

On our first day, we wandered around Barkhor Street in the center of old Lhasa, climbed Potala Palace, and visited a nunnery. From Jokhang temple we had a great view over the city, at that time unaware that in front of its doors a self-immolation had happened just a few hours earlier . The rumors had reached us, we noticed heightened security, but it didn't affect us much and we continued our itinerary as planned.

The taxi dropped us off at one ot the entrances to Barkhor Street. It was the muslim quarter with its huge mosque that welcomed us - quite unexpected!

Pilgrims circulate clockwise around Jokhang Temple, many doing full-body prostrations, others just spinning prayer wheels.

I accidentally captured this pilgrim, only discovered it when looking through my photos afterwards. Very powerful!

In the following few days, we watched monks at Sera monastery debating -more a show for tourists than anything else-, strolled through Norbulingka, the former summer palace of the Dalai Lama, took a bus to Drepung and Ramoche monasteries, and went on a day trip to Yangpachen natural hot spring and Namtso, the largest saltwater lake in Tibet.

Locals maintaining religious buildings. Once built, living quarters and storefronts are often just neglected.

After a few days we left the city. As before, one highlight followed another: we stopped in Gyantse, crossed Kamba-La (4794m) and the Karo-La passes (5010m), and strolled along the turquoise-colored Yamdrok Lake. In Shigatse (3836m) I experienced a mild form of altitude sickness. Luckily the pills that I carried as a precaution helped and I was fine the next day.

In Shigatse we met another small group of travellers who had planned to arrive at Everest Base Camp a day before us. They had just received news that the road leading to EBC has been closed for all foreigners until further notice. Inquiries by our tour guides confirmed the fact with the vague explanation that a foreigner had posted a picture of himself holding a "Free Tibet" sign at EBC. I could never find out if this referred to a recent incident or to a protest a few years ago. Self-immolations as political protest have been going on for years, although the vast majority happened in other Chinese provinces, such as Qinghai, Sichuan, and Gansu. And for Lhasa, it was a first. It was obvious that the government was nervous.

The next day didn't bring better news either, our tour guide Penpa -always smiling and relaxed- apologized and suggested that we stay in Old Tingri until the next day, the best place in the region to get a good view at Mt. Everest and Mt. Cho Oyu. Of course, we agreed, but couldn't deny that we were disappointed by the turn of events.

I've already introduced Old Tingri and its impact on me in my previous article. It's quite a place!

There wasn't much to do. Clouds obscured the mountains for most of the time.

While I was wandering off on my own for a while, three children approached me with the oldest one (maybe 8 years old) standing in front of

me demanding "MONEY!" while the younger ones each grabbed one of my legs making it impossible for me to move. I refused, insisting that I didn't

have any money on me, and eventually they let me go. This was the only time during my 15 months

in China over the last 9 years that I was really scared for a moment. I decided not to go back the same way but to take a "shortcut" up the

hill to meet up with my travel buddies. Easier said than done at an altitude of over 4,300 m!

My 'best' Mt. Everest shot - won't win the shot of the year. Well, when you are at 5000 m then 8000 m doesn't look all that high.

The next day we drove to the Nepal border, where my two companions continued their travels while I returned with our driver and tour guide to Lhasa. We stayed again at the same little guesthouse. Order had been passed out that all foreign tourists must leave the TAR. For me, it only meant that I would return to Chengdu a day earlier than planned – no big deal. But what would it mean for Penpa, the guesthouse family, and all the other small businesses and operations that depend on foreign tourists? At that time, it wasn't clear how long foreigners would be banned. It turned out to be for the whole 2012 season.

The guesthouse owner was desperate. How could she feed her family? How could they survive? Her whole business relied on foreigners. She had been on the phone all morning cancelling bookings and making alternative arrangements for her and her family. Maybe stay with relatives in the countryside for a while?

Penpa's spoken English was good. His friendly and outgoing personality made him an excellent tour guide. His written English wouldn't be good enough for an office job and his Mandarin not sufficient to guide Chinese visitors. How could he make a living?

Being so close to people who are struggling to meet the most essential human needs, without their own fault and despite working so hard and diligently, made me see many things in a completely different light. I see beyond the filth in Old Tingri, I'm not angry at the begging kids anymore, I appreciate my mostly worry-free daily life more, and I feel very privileged that I have a job I can take with me wherever I go.

This blog is about human beings and the short time that I can participate in their lives. My aim is not to make political statements, but since the root of this story is political, let me just say this: The Tibet question isn't as simple as often portrayed in the West. A fanatic who sets him- or herself on fire, doesn't make any positive contribution to the situation in Tibet. As this story shows, it hurts countless ordinary people. A dead person -or someone so severely injured that others must care them for the rest of their life- can't be involved in constructive change anymore. That foreigner's "Free Tibet" picture on Mt. Everest might look cool on Western social media, but it doesn't change anything either, it only hurts local people.

Which brings us back to the mountain. While my love and understanding for all the people that I met on this journey grew, I lost my admiration for the climbers. Not that they are not extraordinary people with unbelievable willpower and determination. It just doesn't feel that important to me anymore.

Mt. Everest has many faces, and this was mine to see and share. Thanks for closing the road to EBC and showing me all the others.

Update: I stayed in lose touch with Penpa for a while. He left Lhasa and accepted an offer to train as a cook in

Shenzhen (southern China, close to Hong Kong). Of course, he missed Tibet, but he made the best out of the situation. Without my photos

I might forget his face over time, but I would always remember his big smile!

Ba-sang, our driver, and Penpa, our tour guide

Afterthought: Another season of madness has reached the Nepali and Tibetan sides of Everest. In 2019 alone, 12 of

the world's fittest people lost their lives in an attempt to stand on top of the highest mountain for just a few minutes. What drives these

people to train for months or years and spend a fortune for that small chance to get a shot at the summit? Is it really so desirable to one day show

a picture like the one below to their grand children, exclaiming '… and I was one of them'?

This handout photo taken on May 22, 2019 and released by @nimsdai Project Possible shows heavy traffic of mountain climbers lining up to stand at the summit of Mount Everest. (@nimsdai, Project Possible/AFP)